A quarter of a century is a considerable historical period, especially for a country, not a person. On the day of the 25th anniversary of the independence of Ukraine, we can say that we are united by common values. We have the army and the nation. What we need is an effective legal state accountable to its people.

One of the most miserable European economies

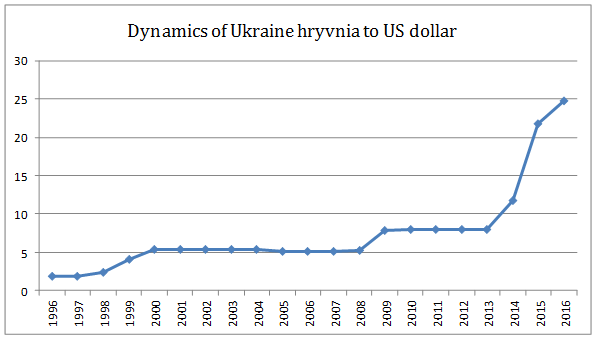

25 years were not enough to create a state, of which millions of Ukrainians dreamt, whatever way they chose. According to the indicator of depreciation of the national currency (by almost 13 times, see Diagram 1) over this period, Ukrainians failed to achieve high living standards or a stable dynamics of economic growth. In 1996 (on the 5th year of Ukraine’s independence), the hryvnia to dollar ratio was 1.82:1. In 2008 (the year of the crisis for many world financial systems), the ratio changed to 5.26:1. In 2013 (on the eve of the Revolution of Dignity), it amounted to 7.99:1. And now, after the two years of the war, it constitutes 24.8:1.

Diagram 1. Dynamics of Ukraine hryvnia (UAH) to US dollar (USD) over 24 years (1992-2016) (1 UAH:1 USD), based on data of the National Bank of Ukraine

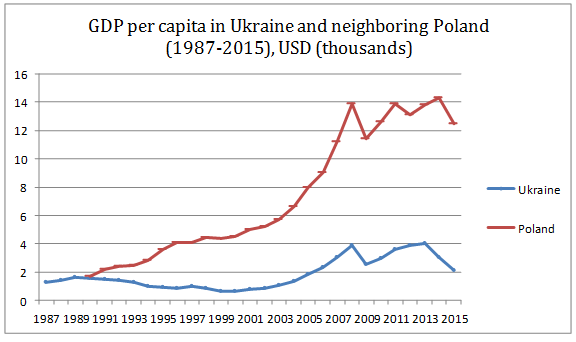

Over the years of independence, Ukraine considerably fell behind neighboring Poland, with which it was on a par in the 1990’s. As seen from Diagram 2, Poles achieved the sustainable growth of GDP per capita (maximum – more than USD 14,000, whereas Ukrainians failed to reach even USD 4,000).

Diagram 2. Comparison of GDP per capita, based on data of the World Bank (http://data.worldbank.org)

Over the years of independence, the population of Ukraine decreased by 7,000,000 people (from 52,200,000 people in 1993). The number of Ukrainians in 2015 was approximately equal to that in 1960, the 15 years after the end of WWII.

In February 2016, Bloomberg ranked 63 economies, of which Ukraine rounded out the top five unhappiest ones, along with the South African Republic, Argentina, and Venezuela (http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-02-04/these-are-the-world-s-most-miserable-economies). Greece was the only EU Member State that appeared in this group because of the high unemployment level.

According to the 2016 Social Progress Index developed by the U.S. Social Progress Imperative, Ukraine ranked 63rd (USD 8,267 per capita) among 133 countries. It led the fourth out of the six groups of countries – lower middle social progress (http://13i8vn49fibl3go3i12f59gh.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/SPI-2016-Main-Report.pdf). No EU Member State was represented in this group.

The above data give the general picture of Ukraine’s economic weakness. And many Ukrainians are miserable not only because of the low living standards but also because of poor governance, stagnation, and the absence of dynamics of economic growth.

The modernization of the state is the call of the times

The “movement in a circle” is the most typical characteristic given by participants in different focus groups, which we hold in different Ukrainian regions to study the attitude of Ukrainians to different socio-political processes, the course of reforms, as well as positions and activities of different political parties. Actually, it often seems that the time has stopped in Ukraine. The political stagnation is associated with the absence of political actions, decision-making and testing their implications in different areas.

The first strategy to overcome poverty was adopted by Kuchma’s government in August 2001 (http://zakon5.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/637/2001). According to it, 26.7% of Ukrainians were poor, while 14.7% lived below the poverty line. The strategy provided that in 2010, the share of poor Ukrainians and those living in extreme poverty would be reduced to 21.5% and 3% respectively. The second strategy to overcome poverty, adopted by Azarov’s government in August 2011 (http://zakon4.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/1057-2011-%D0%BF), said that the level of poverty was 27% in 2010. According to the third strategy for sustainable development “Ukraine-2020”, adopted by Yatsenyuk’s government (http://zakon4.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/161-2016-%D1%80), 23.8% of Ukrainians were relatively poor in 2015. Hence, it took the country 15 years to reduce the level of poverty by just 3%. And it is not necessarily true that this was achieved thanks to the efforts of the government.

The fight against corruption is another “déjà vu”. It was a launching pad for many Ukrainian politicians. Millions of dollars of international aid were spent for anti-corruption activities. Yet, some tangible changes occurred only after the Revolution of Dignity that rejected corrupt authorities. Changes in the system of power, acrimonious political struggle, transparent government procurement, development of a financial monitoring system, disclosure of information on beneficiaries, and electronic means of access to information help make the public aware of the decision-making process. Of course, this is not a transparent government capable of making effective procurement. Yet, in the post-revolutionary fervor, we set up five government agencies that compete with each other in the fight against corruption. There is a great difference between the new system and the old corrupt one, under which the taxpayers paid for the wellbeing of decision-makers. Today, it is necessary to question the effectiveness of the state, and the price it pays for decisions made.

The political renewal

It may seem paradoxicallybut the largest tragedy of the period of Ukraine’s independence, the war in the Donbas, helps understand changes in the country. The war made Ukrainians reconsider their attitude to each other, to sovereignty as a phenomenon, and to the state as an indirect mechanism of relations that needs to be built and developed. Oleksandr Paskhaver, Ukrainian scientist and economist, said: “Having no nation state, Ukrainians have long perceived it as something alien” (Make Haste Slowly, the New Time; 20 August, 2016: http://m.nv.ua/opinion/paskhaver/speshit-medlenno-199985.html). Now is the time to ask questions how to modernize the state,how to rationalize its structure and activities,how to ensure the legitimacy of its actions, and the prevalence of law and order. The recognition of the rule of law and the priority of human rights in government policy-making will help Ukraine adopt the European culture of law instead of Byzantinism, and become more understandable and predictable, first of all, for its own citizens.

Moreover, the war clearly shows the differences between today’s Russia that aggressively continues its imperial policy and Ukraine that identifies itself as an integral part of European ecumene and officially declares its aspirations to be a part of the European Union, and a security element in the continent. Every time Ukraine started rapprochement with the EU and NATO, Russia actively opposed this intention. Specifically, the cassette scandal and the notorious murder of journalist Georgiy Gongadze discredited Leonid Kuchma, who even nominally rejected the idea of Ukraine’s integration into the EU and NATO in 2004. Besides, the avoidance of a consistent policy of European integration, personal and business relations and ties of top Ukrainian politicians with the Kremlin considerably slowed Ukraine’s pace towards a European economic model and strategic political partnership.

The current war in the Donbas, which erupted in April 2014 after the annexation of Crimea, was not an expression of Vladimir Putin’s fear of the distribution of a “virus of colored revolutions”, but a signal to the world that Ukraine is in the focus of Russia’s interests. Independence cannot mean isolationism. Anyway, Ukraine needs to find its place in the world and in Europe, promote its new technology business, and become a part of the European security architecture. And now Ukraine can do and is doing this by preventing the spread of the “Russian World” on its eastern border.

In contrast to the Baltic States, Poland, and the united Germany, Ukrainian politicians managed to avoid political lustration in the early 1990’s, and many of current political figures belong to the power elite of 1995-2000. Nevertheless, the political renewal process was launched. Three out the eight convocations of the Verkhovna Rada elected at the special parliamentary elections in 1994, 2007 and 2014, the annexation of Crimea, the war in the Donbas, and the 2015 ban on the Communist Party preventing it from operating and participating in elections – all these taken together accelerated changes in the political environment. It is the Ukrainian society that will determine the essence of these changes, and the pace of the political renewal.

By Svitlana Kononchuk and Maria Diachuk, UCIPR

UCIPR, Research UpdateVol. 23. - №3 (756), 24 August, 2016